The Other Side of Bintan

Perhaps the thing that worried me most about Bintan – especially in the days just before I went on assignment – was the fact that I had no idea what my story was all about. Not that there wasn’t a general framework: I knew that I’d be going from the north to a newly-opened property on the southeast coast, and Iris and her crew at Bintan Resorts had planned a detailed itinerary of things to do and places to see. But would the island as a whole be interesting enough to fill out a print article of just over 2,000 words? And would I be able to find and talk to the right people? Most of all, I was hoping to find a central idea or metaphor that would help reveal an integral part of Bintan’s character, capture its essence, or at least give readers a stronger sense of place. So when Iris recounted a colorful local legend on the second night of the trip, as we sped down dark country roads in a van back to the hotel, I knew that I had struck gold.

One of the most popular stories from the Riau Malays’ rich oral tradition is the tale of Lancang Kuning. The legend differs depending on where you go in Sumatra and the Riau Islands, with the darkest version involving a love triangle between a beautiful maiden and two trusted commanders of a local king. It is a shocking account of deceit, black magic, and a magnificent royal ship – the Lancang Kuning – that cannot be launched without the human sacrifice of the pregnant and recently-wed love interest. In the end the king and both his commanders meet their deaths; the proud kingdom ceases to exist and the Lancang Kuning is lost in a tempest. It illustrates how a personal vendetta can spiral out of control and lead to the destruction of an entire nation.

Another, more palatable spin on the tale speaks of Si Lancang, a boy who grows up in abject poverty with his widowed mother near Sumatra’s Kampar River. He decides to seek his fortune elsewhere, promising his mother to return once he has accumulated great riches. Si Lancang eventually becomes a wealthy merchant, but when his luxurious trading ship makes a stop in his hometown, he denies his tattily dressed mother (“I do not know this crazy old woman!”) in front of his seven wives and expels her from the vessel. Upon returning home, the brokenhearted woman cries out to God to punish her ungrateful son. In that instant, a powerful storm materializes, tearing the ship to pieces and sinking it with the loss of all on board.

The version told in Bintan is much simpler and comes without the moral message of its Sumatran counterparts (which suits me well because I too, unfortunately, have left my dear mother at home). Instead, Lancang Kuning refers to a phantom ship – purportedly built by the seafaring Bugis from distant Sulawesi – that is said to be visible in the shallow waters off the island’s northern coast. According to local legend, the mysterious shipwreck rises from the bottom of the sea every 10-15 years, typically for a few days at a time. “Almost all the resort staff who have worked here for a long time say they’ve seen it,” Iris explained. “People have tried to find it in the past, but it was always submerged and covered by sand.”

Soon after setting out on a cross-island journey the next morning, I asked our guide and driver Maradu about the phantom ship. He’d been living in Bintan for the past 18 years and Lancang Kuning had last been sighted as recently as 2016. “I went down to the beach at Mayang Sari, but I couldn’t see it even when my friends could,” he told me. “It could be because I don’t believe in this kind of thing. Or maybe it’s because I’m not Malay. But they say if you are really longing to see it with your heart, then it will reveal itself.”

Halfway through the trip, Iris and Maradu had furnished me with the central metaphor I had been seeking all along. I soon realized that Maradu’s words about Lancang Kuning could also be applied to Bintan as a whole – the island would reveal itself to whoever longed to see and understand it on a deeper level. Cruising the Sebung River on a “mangrove discovery tour” the previous day had opened my eyes to the beauty of its native flora and fauna, and now I was ready to get a closer look at Bintan’s fascinating past.

When we think of pirates in a historical context, it is likely the 17th- and 18th-century Caribbean that springs to mind. But Bintan had already developed a reputation of being a favored haunt for pirates some 500 years earlier. By the time of Ibn Battuta (who sailed the nearby waters on his epic journey to and from China), opportunistic locals preyed on passing merchant ships laden with silk, porcelain, spices, and other precious cargoes. Bintan was a natural choice for a hideout thanks to its strategic position on the maritime trade route between China and India; anyone who came from the Strait of Malacca just 56 nautical miles to the west would have to navigate the narrow Singapore Strait, skirting the island’s northern coast before entering the South China Sea.

I don’t come across any traces of that piratical history, but southern Bintan is peppered with reminders of its prior importance in the Malay World. The founding of a new settlement at Sungai Carang in 1673 marked the dawn of a golden age for the island. What was intended as an offshore fortress of the Johor Sultanate developed into a buzzing entrepôt for regional trade, so much so that the Malay term “riuh”, or boisterous, gave its name to the boomtown, Riau, and the surrounding island group. And when the old capital of Johor was sacked in 1722, the sultan moved his court to Riau – where it would remain for the next 65 years.

The scant remnants of Riau’s onetime palace still dot a park by the upper reaches of the indented harbor at Tanjung Pinang, by far the largest settlement on Bintan and the provincial capital of the Riau Islands. It’s a low-rise city of over 200,000 residents that sprawls across a peninsula of gently rolling hills, but there aren’t any regular taxi services as you would find in larger urban centers, and aside from two branches of KFC and one Pizza Hut outlet, American fast food and coffee shop chains don’t have much of a presence. McDonald’s and Starbucks have yet to open stores here.

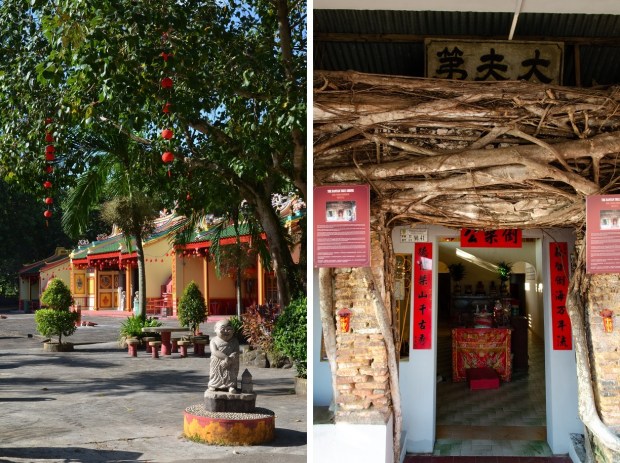

Roughly 20 percent of the population on Bintan is ethnic Chinese, and nowhere is this more apparent than in the older parts of Tanjung Pinang, where I encounter plenty of people with faces much like my own. There are prized, jet-black sea cucumbers being sun-dried in rattan baskets atop small stands out on the sidewalk; lunch at a no-frills eatery means kwetiau noodles with juicy prawns, all imparted with an aromatic, smoky flavor from being stir-fried in a blisteringly hot wok. And being February, the streets are festooned with lanterns ahead of Chinese New Year. But the real reason I’ve come is to hop aboard a slender pompong boat for the 15-minute ride to Penyengat Island.

By the early 19th century, the British and the Dutch had long been engaged in a game of one-upmanship to dominate the region and the maritime trade flowing through the Strait of Malacca. When Johor’s Sultan Mahmud Shah III died in 1812 with no heir apparent, both countries took advantage of the ensuing crisis to ensure that the throne would be occupied by a new sultan of their preference. It was in this political climate that Stamford Raffles signed a formal agreement with Hussein Shah, Britain’s favored pick, to establish the new colony of Singapore and effectively split Johor in two. That partition was formalized in 1824 with the signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty: the two powers agreed that mainland Johor and all its territory to the north of the Strait of Malacca would fall under British rule, while the Riau Islands would go to the Dutch.

Tiny Penyengat Island then became the seat of the Dutch-controlled Riau-Lingga Sultanate, a status it held for almost a century. But the erstwhile center of power is now sleepy and half-forgotten. About 60 percent of the local population is still descended from Malay royalty, though you wouldn’t know it from the humble appearance of their village houses. Soon after arriving at the pier, I take a guided tour of the island’s main sights in a boxy motorized becak (rickshaw). We visit the Balai Adat Indera Perkasa, a large stilted meeting hall built in traditional Malay style; the grounds of the two-story shuttered palace (more akin to a large house); and the ruined fortress atop Kursi Hill a short walk away. Also on the itinerary are the well-tended tombs of Riau’s former rulers scattered around the island, all of them brightly painted in the universal Malay colors of green – denoting Islam – and yellow, which represents royalty, grandeur, and luxury.

There’s a reason why so little remains of Penyengat Island’s regal history. In 1911, as hundreds of Dutch colonial troops launched an assault to force an end to the sultanate, the court of Sultan Abdul Rahman II torched their buildings to stop them from falling into enemy hands. Only the Grand Mosque was spared. Abdul Rahman II and his queen were exiled to nearby Singapore, followed by the crown prince and their loyal supporters.

Bintan is full of such stories – you only need to know where to look. The next day, at the airport named after 18th-century sultan Raja Haji Fisabilillah, who lost his life in a successful raid against the Dutch, I find yet another reference to the local history inside the gleaming glass-and-steel terminal. One wall has been solemnly inscribed with the Gurindam Dua Belas, a celebrated poem penned by the hero’s grandson Raja Ali Haji on Penyengat Island. Raja Ali Haji wasn’t just any sultan: he was also a prolific author, poet, and historian who gave the Malay language its first modern dictionary. It is then, while waiting for my flight back to Jakarta, that I finally understand how Bintan’s past may hold the very keys to its future. ◊

Gorgeous photos — and this piece was written in the spirit of a true traveler.

Thank you, Kim! I realize this was a long post and a deep-dive into the history and folklore of the place, so I’m grateful you read through the whole thing.

James I too sometimes am concerned that I will be able to come up with the story. In this case I love that you listened and heard the them,.. it will reveal itself. So many stories in one and your gorgeous photos jammed with vibrant colours make this reader definitely want to visit.

Glad you enjoyed it, Sue. I imagine Bintan will be a great place to explore by bike, being quite sparsely populated (by Asian standards anyway!) and not having much traffic except in downtown Tanjung Pinang.

Indonesian folklore can indeed sound too harsh and difficult to digest, and if there were such a thing as a folklore audience rating, many stories would have been classified as PG-13 or even R for the amount of violence involved. Anyway, this is a really nice post on the other side of Bintan most people are probably unaware of; the heritage buildings, the cultural sights, and your interesting story really piqued my interest of this island, one of those places in Indonesia I was previously never interested in visiting. It’s really nice to read about the etymology of Riau, which makes me wonder about how other Indonesian provinces got their names.

I too was surprised by the origin of the name Riau and the gory/dark nature of Lancang Kuning’s “R-rated” version, which seems to be most popular in Pekanbaru. Thanks so much, Bama – knowing your penchant for history, I would love to revisit Bintan with you on a short break from Jakarta!

How interesting to have all these different spins on this legend (I’m sure you are nothing like the terrible son in the Sumatran version!). Fascinating tale and an interesting place. Isn’t it great when a story idea crystallizes!

Absolutely, Caroline! I think I felt the pressure much more because this was for work and not the blog. It’s so different when you’re being paid to do it and your boss has high expectations.

Well, my mother has been wanting to trek the last 100km of the Camino de Santiago with me for years now, and when we came very close to going in 2014 we had to cancel (with a 50% refund) because I couldn’t take time off from a documentary project for my masters. Now that we’re living in different countries I don’t quite know when this will happen, and she isn’t getting any younger!

I know, it’s so challenging trying to find time these days. But I hope that you’ll do the Camino with your mom. As a mom myself, I can tell you that nothing makes me happier than spending time with my son who is now across the other side of the country – a 5 hour flight away.

This was a great read – so much history in such a small place. The story always seems to present itself doesn’t it? And we each have our own way of seeing a place. I’d love to go exploring in amongst the stilt houses, and ride in the boats all around the settlements. Lovely photos as usual.

Alison

Thanks so much, Alison. I completely agree; the story will naturally come to us as long as we remain observant and inquisitive and interested in our new surroundings. I’m certain you would take some wonderful portraits in the stilt villages of Bintan – you have such a knack for capturing the faces of local people.

James

That island has a lot going on – mosques, churches, Chinese temples, beaches, villages. Would it be worth a long weekend trip if say a person were living in Bangkok?

Personally, I think it’s a bit too much effort to get there from Bangkok purely for a long weekend. It’s fine for Singapore and Jakarta because there are direct connections to both (Singapore by fast ferry, and Jakarta by air). Bintan is perfect if you have an extra few days in Singapore and you’d rather go somewhere bigger and wilder.

Makes sense. There are places near Bangkok that aren’t necessarily worth a visit unless you live here and need a weekend out of the big city.

Ran across your piece on Bintan. Inspired me to explore explore Singapore nearby islands. Hope can do this once the Covid 19 thing is over.

Thank you for reading and writing down your thoughts… fingers crossed the current Omicron wave will be over soon!