An Ode to Opor

Food has enormous potential to connect and unite people, to cross the barriers of language, race, and creed. There is power in the simple act of sharing a meal with people whose backgrounds are different from your own. For what better way is there to understand a place than to meet the local people and eat their traditional cuisine? A shared interest in cooking is the basis of a special bond I have with Bama’s mother, who I call Auntie Dhani. “She loves seeing people enjoying her food,” Bama told me recently. “And no one appreciates it like you do.” Of all Auntie Dhani’s exquisite kitchen creations, my favorite is opor, a curry-like stew of poultry, usually chicken, braised in a medley of spices and coconut milk.

The first time I ever tried opor ayam (chicken opor) was in late 2014, during a dinner with high-school friends at a now-shuttered Indonesian restaurant in Hong Kong. I had read about the Javanese specialty in one of Bama’s earliest blog posts, which featured a mouthwatering photo showing his mother’s home-cooked opor: pieces of lean chicken half-submerged in a vivid yellow sauce adorned with slivers of fried shallot. So, you can imagine my sheer delight at finding it on the menu. But when the plate of opor ayam arrived at the table, I was sorely disappointed. This restaurant’s version was pallid, extremely watery, and lackluster in flavor. Surely this couldn’t possibly be the same dish Bama had described with such fondness?

That said, practically every Javanese family has its own recipe for opor. Some insist on using turmeric to give it a telltale golden hue; others prefer to keep theirs a whitish-brown color, closer to the one I’d sampled back in Hong Kong. What that restaurant menu did not mention was its cultural significance as a festive dish. Opor is eaten all across the island of Java – home to more than 140 million people, or more than half of Indonesia’s total population – during Idul Fitri (a.k.a. Eid al-Fitr), which marks the end of the Islamic holy month of Ramadan. And one particular element of opor is imbued with meaning. The Javanese word for coconut milk, “santen”, rhymes with “pengapunten”, the formal term for “forgiveness”. Idul Fitri is traditionally a time when many Indonesians patch up broken relationships; not for nothing is the prevalent greeting “maaf lahir batin”, or “forgive me for what I have said and done”.

Naturally, it was during Idul Fitri five years ago that I first tasted Auntie Dhani’s opor at her home in Semarang, the sleepy provincial capital of Central Java. Lifting a spoon to my lips, I closed my eyes and took a deep whiff of the pastel-yellow sauce. An intoxicating fragrance immediately washed over my olfactory receptors. What was this wondrous perfume? I don’t know how else to describe my memory of that particular aroma, except to illustrate it in this bucolic tableau: a grove of fruit-laden coconut palms, coriander and cumin drying on mats in the equatorial sun, free-range chickens roaming the fields below a Javanese volcano, clumps of lemongrass beside a bubbling brook. It was a revelation. On the tongue, the opor felt smooth and perfectly balanced in more ways than one. Auntie Dhani’s expert blend of spices, herbs, and seasonings did not overwhelm the palate; the soupy sauce was neither too thick nor runny like water.

Some of the ingredients used in Auntie Dhani’s opor: shallots, garlic, salam leaves, lemongrass, and turmeric

Dig deep enough and you’ll find that just about every celebrated Indonesian dish has a fascinating backstory. Rendang, the dry meat curry created by West Sumatra’s matrilineal Minangkabau people, is said to last up to a month without refrigeration, providing fuel for the long journeys undertaken by young Minang men as they sought wealth and knowledge abroad. The origins of opor are no less intriguing. Some scholars posit that it began as an offering from the Javanese elite to their kings in pre-Islamic times, especially when the monarchs toured distant corners of their realms. Other historians say the festive Javanese dish bears culinary influences from India (through the use of turmeric) and the Arab world. Perhaps the latter was deduced from the presence of spices like cumin and coriander seed: cumin’s native range corresponds to modern-day Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan, while coriander traditionally grew in a vast arc from the Eastern Mediterranean through what is now Pakistan. But did Persian and Arab traders introduce these two spices to the Javanese pantry? Or were they actually brought over from India? No one can answer this question with absolute certainty.

Auntie Dhani told me she learned to make opor from her late stepmother and sister-in-law, whose repertoire spanned a host of traditional Javanese dishes, many of which Bama’s notoriously picky father had grown up eating. “She was an even better cook than I am!” Auntie Dhani exclaimed. As her kitchen skills improved with time and practice, she began analyzing the flavors of different kinds of opor and perfecting her own recipe through trial and error. I’d brought along a notepad to jot down Auntie Dhani’s version so I could try replicating it at home. But she had to think carefully when I asked her about the precise amounts of each ingredient. For her, weights and measures were not necessary no matter how elaborate the dish. “I use my feeling,” she’d say.

There are several reasons why Indonesian food doesn’t travel well beyond the country’s borders. One is the difficulty of finding certain Southeast Asian ingredients abroad. Another is the labor-intensive approach to cooking that requires patience and a commodity so many of us lack in our increasingly busy lives: time. Opor is not something that can be whipped up in 15 minutes or half an hour; nothing about the process should be rushed. Auntie Dhani showed me how the spice paste is sautéed in hot oil over low heat, constantly stirring so it doesn’t burn. “The candlenut takes the longest to ripen,” she explained. “If you cook it too fast, the smell is still raw, and that breaks the flavor of the dish.”

In a way, Cantonese and Indonesian cuisine could not be more different. The former is far more produce-driven, emphasizing both the freshness and quality of its main ingredients, and the seasoning deliberately restrained to bring out their natural flavors. Growing up in Hong Kong, I often ate steamed fish marinated in soy sauce, strips of ginger, and perhaps some chopped scallion. To this day I harbor a latent dislike for bok choy, because the only way my family ate the leafy Chinese vegetables was to have them boiled with no added salt or other flavorings. In contrast, Indonesian food relies heavily on the use of bumbu (pronounced boom-boo), a foundational spice paste that gives each dish their complexity. The simple explanation for why Indonesian nasi goreng tastes completely different from Cantonese fried rice is that one has bumbu while the other doesn’t.

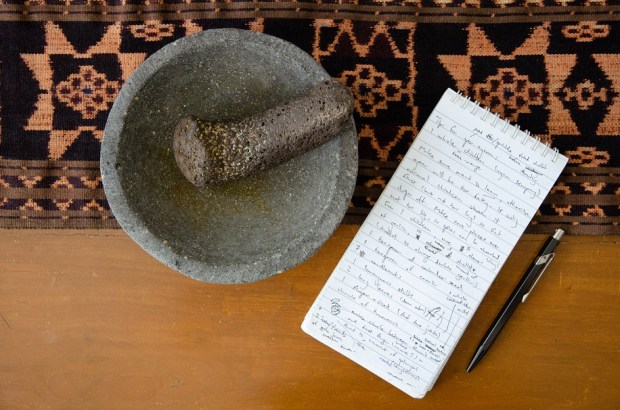

Auntie Dhani’s opor ayam became my window to a whole new world of cooking. She taught me what it was to harness spices and play them off each other, to use their contrasting flavor profiles in complementary ways. And there’s no better way to prepare the bumbu than with a mortar and pestle. Some professional chefs swear by this method (as opposed to using a blender or food processor) because it releases more natural oils. Though the process takes much longer, there is a certain joy and satisfaction to be found in pummeling spices and aromatics by hand, mixing their aromas and turning humble ingredients into a satisfying blend that is ultimately greater than the sum of its parts.

Armed with Auntie Dhani’s recipe and a few of her expert tips, I began to make opor at home in Hong Kong. The first iteration wasn’t an abject failure, though I made a mistake that was unthinkable for any Indonesian chef. This involved the use of daun salam, or Indonesian bay leaves, known to release a distinctive herbal, woody aroma. One Philadelphia-based blogger, a talented home cook in his own right, says that salam leaves add “a subtle yet unmistakable sweet and savory flavor … between cardamom and cinnamon.” But because it was conspicuously absent in supermarkets, I substituted the daun salam with kaffir lime leaves, which had the effect of completely changing the opor’s overall flavor profile. Bama was both shocked and amused when I told him what I did: “If you can’t find daun salam, it’s better not to use anything at all.”

I had better luck the second time, thanks to a bag of dried, almost blackened, salam leaves I had picked out from the freezer of a small Indonesian corner store. My brother said it was more flavorful than the first try, but when I brought it to my grandparents’ apartment for Christmas dinner, the extended family disagreed. Mo mei geh? My food-loving granddad asked. “Why doesn’t it taste of anything?” The reason was that I simply hadn’t added enough salt.

“When you’re cooking soupy dishes,” Auntie Dhani told me roughly six months later, “you must be brave [to use more].” However, it was also about knowing when to stop and finding the right balance between sweetness, saltiness, and fat. I watched intently as, bit by bit, she crumbled round discs of unrefined coconut sugar into her bubbling opor. In between each addition, Auntie Dhani tasted the sauce until it had reached its desired flavor.

After I moved to Jakarta four years ago, my trips to Semarang with Bama became an annual pilgrimage during the week-long Idul Fitri holiday. Each year I tried to add one or two more recipes to my notebook. Eventually, Auntie Dhani gifted us an ulekan, a mortar and pestle made of heavy volcanic stone – specifically black andesite, the same material quarried from the earth to build ancient Javanese temples like Borobudur and Prambanan. Pockmarked and worn from years of repetitive use, the spice-grinding implements occupy a special place in our kitchen.

It wasn’t until January this year that I worked up the courage to cook opor for the ultimate judge: someone who had eaten it from a very young age. Was I going to ruin Bama’s beloved childhood dish? And could I meet the exceptionally high standards set by Auntie Dhani? Perhaps I was only setting myself up for disappointment. Any similarity with the original recipe, I reasoned, would count as a bonus. But I was surprised by the final verdict. “I would say it’s more than 90 percent there. It just needs a bit more salt,” Bama said. He took a snapshot with his phone and sent it to Auntie Dhani, who complimented my creation on its beautiful golden color.

The next morning, when I served the dish after adding several sprinkles of table salt as it warmed up on the stove, Bama stopped abruptly after taking a sip of the bright yellow sauce. “This tastes exactly like my mom’s cooking,” he marveled. Unbelievably, Bama was right. Once the creamy opor hit my taste buds, I was transported back to Auntie Dhani’s home in Semarang and that clear, sunny morning of Idul Fitri. ◊

Awesome log post

Thanks for reading!

Auntie Dhani sounds like a real cook (love the fashionable pose!). Loved the food photos and I’d like to try opor one day.

Your photo with the shallots send shivers down my spine. Better Half loves shallots but I think that the ones they sell ’round here are also used by police for manufacturing tear gas… I dice three and I’m normally blind of 15 minutes.

Ha! I’d say that peeling shallots for opor is worth the pain, though the small ones here in Indonesia aren’t nearly as tear-inducing as larger shallots from Europe. I reckon you’d love this particular version of opor. It is something of an outlier in Javanese/Indonesian cooking because it doesn’t use any chilies or black pepper. Most Indonesians love their food spicy!

This dish sounds amazing — my taste buds tingle! Your post reminded me of pilau and biryani because like opor, there are so many varieties and I have arrived at a stage where I will never eat them in any restaurant unless it’s located in Gujarat or my own kitchen. Congratulations on persisting to create the exact opor flavour.

Much appreciated, Mallee! I found myself nodding along to your comment – your stance on pilau and biryani mirror my own feelings about opor. The variations I’ve tried from several eateries here in Jakarta have all fallen short in some way. One had the gorgeous golden color but lacked a certain depth and complexity; another needed a lot more palm sugar because it was too salty.

What a sweet story. The dish sounds especially delicious (maybe because it does not have those typical Indonesian hot chilies!), and I just loved the whole history you have with the opor and Bama and his mother (and even the setting of that first tasting at Bama’s family home). Like Fabrizio, I noticed those much smaller shallots, and I wish we had those dainty things here. The preparation looked daunting from the photos of the ingredients, and I’m glad you acknowledged the time and effort it takes to make this! Last but not least, congratulations for winning over your most critical taste-tester!

Thanks so much, Lex! I was really not expecting Bama to be impressed with my take on his mother’s opor. The whole process isn’t nearly as daunting as you might think… though you do need a free afternoon to make the dish from scratch. Grinding the spices in a mortar and pestle can be hard work but lots of fun. There’s a couple of other ingredients – like lemongrass and galangal and salam leaves – that don’t require chopping or crushing: they’re just thrown into the pot when you add water to the cooked spice paste.

I think opor (done properly) would be a great introductory dish at any Indonesian restaurant. As you rightly pointed out, the absence of hot chilies makes it approachable for those of us who didn’t grow up eating spicy food. Funny thing is, whenever my siblings and I misbehaved as children, my mom used to give us a spoonful of chili sauce. I doubt that would count as punishment for Indonesian kids!

Early on in your post I was already thinking that I’d love to recreate this dish. The flavours of lemon grass, garlic, coconut milk, fried shallots, cumin…are among my favourites. I wasn’t surprised to read though that these types of recipes don’t “travel” well. I’d cut corners using pre-ground spices and doubt I could find salam leaves. But thank you for taking me on this beautiful journey of food, culture, history and relationships. I’m sure you made Auntie Dhani and Bama proud.

It was interesting reading about your experience with salt. I have an Indian cuisine cookbook written by Vikram Vij, a favourite Vancouver-based chef. I’m shocked by the amount of salt in many of his recipes, and have until recently used only a fraction of the recommended amounts. The end result was usually good but not awesome. When I was finally “brave” enough to follow the recipe, my family couldn’t believe the difference.

Lovely post, James!

Caroline, I really enjoyed reading your anecdote about making Indian cuisine from Vikram Vij’s cookbook. My own mom taught me to use salt sparingly (or not at all), so being “brave” with it was a big adjustment. And I’m still learning. Just yesterday I watched a Netflix food documentary that said salt has the unique trait of bringing out the flavors of all the other ingredients and “making them taste more like themselves”. That definitely happened with the opor. In hindsight, I can’t fault my extended family for saying my previous version was bland!

For a moment, I toyed with the idea of publishing the full recipe as part of this post, but then I was confronted with two questions. How could I explain the exact quantities of salt and palm sugar when the only way to know is by tasting it in person? And then I wondered about the availability of herbs and aromatics like salam leaves. The other two ingredients you’ll likely have trouble finding in Canada are palm sugar (preferably in a solid rather than powdered form) and candlenuts. Some recipes recommend substituting macadamia nuts but they just taste and smell different. I wonder if Vancouver has any Indonesian grocery stores or bona fide Indonesian eateries… they must get their spices from somewhere!

It’s amazing what you can find in Vancouver, but it takes some effort.

I just read your comment to Alison. Can I invite myself? If you come here, I’ll make you one of Vij’s recipes (with the recommended salt quantity), or better yet, we’ll go to his restaurant.

Of course, Caroline! I haven’t been to Vancouver for far too long – my last trip to BC was more than a decade ago. Judging by some of the photos I’ve seen, I’m not sure I would even recognize parts of the city.

This was a surprisingly delightful read James. Well because you’re such a good story teller. I wouldn’t normally be that interested in a food post, and especially not one about a single dish, but you held my attention from the beginning and now I think I must come to Jakarta and have you make opor ayam for me. It looks and sounds delicious.

Alison

Thank you so much, Alison – those words mean a lot to me. I’ve been away from the blogging world the past two months and it is so nice to finally publish something after a long hiatus. I have an even better idea. Perhaps we should meet in Bali… I do know someone who runs a cooking school in Ubud so maybe I could teach you and Don to make opor there. Either that or I’ll have to come to Vancouver and sneak in some of the hard-to-find ingredients!

I’m a huge fan of either of those plans!

I really enjoyed this story. It’s going to be one of my favorite stories you’ve written. I’ll have to check out the links you’ve included later. I also enjoy the pictures you’ve taken and the history / cultural lessons you’ve added. I’m curious if the opor tastes better overnight? I know some stews are like that.

Thanks for sharing this story.

p.s. I don’t like plain bok choy unless the other dishes are very salty / spicy.

Thanks, Matt! I’m thrilled to hear that you enjoyed this post so much. Bama tells me a lot of Indonesians take opor for granted – approaching the dish as an outsider has made me more curious about its origins and philosophical meaning. I can confidently say that opor tastes exactly the same the day after it’s cooked!

P.S. That makes a lot of sense… I will eat bok choy if it’s cooked with meat or served with abalone.

When I showed the photos I took of your opor to my mom, she said the color looked right. If she were there to taste it, I’m sure she would have agreed with me that it was just like hers. I must admit I was one of those Indonesians who have been taking this dish for granted. We grew up eating it for special occasions, and it’s relatively easy to find at canteens and restaurants, although I’ve always known that my mom’s version is much more special and tastier. Now let’s talk about all those crazy ideas of yours of incorporating opor flavors into other dishes — dim sum, nasi goreng and whatnot. I wonder what my mom would think of that!

Well Bama, I have to thank you for introducing me to Javanese food and your mom’s extraordinary home cooking. There is no way I would have come to understand spices without her help. As for the experimental takes on opor, I did try making nasi goreng with the bumbu in Hong Kong one time – it was delicious! And something tells me that putting opor inside a Chinese-style dumpling would just make sense.